The process of getting into optometry school is inherently anxiety producing. When combined with life’s other 24/7 stress and distractions, it’s no wonder that I get so many distress calls from applicants—especially about the OAT and the stress of objective test-taking. In the past, I would listen compassionately and offer what I thought were practical tips to help better their OAT test performance.

In retrospect, it’s possible that I just made them doubt themselves more and made their anxiety worse.

My response to those stressed-out applicants was a typical example of how Westerners deal with stress. We Westerners take pride in our deductive reasoning, our analytical and linear thinking. We are dualistic with our rationale, meaning that such reductionist thinking renders everything

“. . .made them doubt themselves more and made their anxiety worse.”

Photo purchased from iStockphoto.com

to only black or white. We think the best way to tackle a stressful situation is to buck up and mount a full frontal attack. If that doesn’t work, we do a 180-degree turn, and opt for numbing our anxious feelings with mindless, pain-extinguishing behaviors like drugs, alcohol, sexually acting out, and perhaps the more-socially-acceptable cartons of Haagen Daazs ice cream.

Perhaps because Westerners have hardly any traditional accepted practices to deal with anxiety, we have been taught to react to stress in ways that only reinforce anxious thinking and encourage acting out as an acceptable means of dealing with stress. It is my contention that stressed-out applicants need help that the collective Western mindset just cannot provide.

To help stressed-out, anxiety-ridden applicants—and for my own personal growth when dealing with stress—I found the answers in Eastern traditions: namely, mindfulness practices.

Am I ragging on Westerners? Not really. When faced with a challenge, Westerners rely on external means to deal with stress. It’s our “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” thinking that has served us well in a modern society. However, for the postmodern society that we find ourselves in now, these traditional methods are sadly lacking. While Westerners are conditioned to deal with stress by turning to outside means, Eastern philosophy teaches just the opposite—when faced with life’s challenges, their traditions teach them to go inward. Click here for a chart that compares Eastern and Western thought practices.

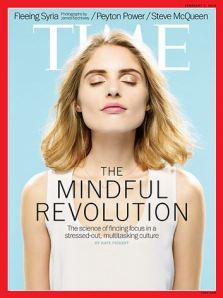

TIME MAGAZINE ARTICLE ON THE BENEFITS OF MINDFULNESS:

I’m not alone in my observations. A February 2014 Time Magazine article, “The Art of Being Mindful” describes a growing trend toward adopting Eastern practices to find peace in what the article’s subtitle rightfully identifies as “. . . a stressed-out, digitally dependent culture.” It cites a growing body of evidence that proves that doing things mindfully by using Eastern practices has great benefits to help alleviate stress, which is of special interest to me as an admissions adviser who frequently must sooth anxious applicants.

The article features the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, a MIT educated scientist and professor who has managed to sell mindfulness to a Western audience through his brainchild, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Currently, there are 1,000 certified MBSR instructors teaching mindfulness techniques (including meditation) in nearly every state and 30 countries. With the nearly pathologic distractions of popular technology and Westerners’ positive reinforcement of compulsive multitasking, he is meeting an obvious need for mindfulness. However, it’s a hard sell to Western culture because it requires shutting down our need to keep in constant touch with the outside world. This is especially true for Millennials who love being constantly plugged-in, and may see little benefit in doing just one thing at a time or being in only one place at a time—both of which are basic tenets of mindfulness.

The article’s author, Kate Pickert, agrees to be a guinea pig for MBSR training. To begin her journey into learning the path to mindfulness, she needed to break old habits by learning how to quiet her mind—to downshift, so to speak. To shift her brain into this lower gear, she needed to learn how to meditate, which became her first hurdle. Before any instruction on meditation, she had to be coerced into turning over her iPhone, Blackberry and laptop. She describes her first attempt at meditation as an experience that was an “agonizingly frustrating period,” lasting 40 minutes, where she struggled to focus on her breathing, and all the while, being bombarded with invading negative thoughts.

Let’s just say that she didn’t have a successful introduction to the art of becoming mindful. But that would change.

The next evening the group engaged in another exercise called mindful walking, which proved to be the ticket for her. Mindful walking proved to be her baby step towards mindfulness: it served to keep her hyper part occupied while at the same time, quiet her mind. I can relate to this being the hyper person that I am. I was introduced to mindful walking through a method taught by Thich Nhat Hahn. In his booklet, The Long Road Turns to Joy, he describes walking meditation:

Walking meditation is meditation while walking. We walk slowly, in a relaxed way, keeping a light smile on our lips. When we practice this way, we feel deeply at ease, and our steps are those of the most secure person on Earth. All our sorrows and anxieties drop away, and peace and joy fill our hearts. Anyone can do it. It takes only a little time, a little mindfulness, and the wish to be happy. ~ Thich Nhat Hahn

I describe mindful walking as a slow, deliberate pace, where you are intentionally aware of all the sensations around you. Fully present, you shut off the part of your mind that wants to obsess about the past or present, and adopt a peaceful awareness of all the sensations present in your surroundings: nature’s colors, its smells, its sounds, and the awe of it all.

“I describe mindful walking as a slow, deliberate pace, where you are intentionally aware of all the sensations around you.”

Photo purchased from iStockphoto.com

The combination of a motor activity coupled with a mindful state proved to be a winning combination for Kate. It helped bridge the gap by helping her body shift gears more smoothly. It helped her buy-in. The mental state she achieved through mindful walking helped her with the key objective of any mindfulness practice: the point at which one begins to recognize just when his or her mind’s focus vacates the moment. During any mindfulness exercise, it’s a given that your mind will wander off. It’s being able to recognize when that departure occurs and then gently prompting your thoughts to reestablish their focus. This cycle happens over and over. It’s like what happens when you’re reading and lose focus. Instead of digesting the information, you instead are just skimming the words. When you make the discovery that you’ve lost focus, you retrace the reading material to find the place where your mind left the process of interpreting the words you were reading, and you pick up the reading process again with the intention to maintain focus—but alas, it happens again and again.

“Our culture does not reinforce the advantages of staying in the moment.”

Photo purchased from iStockphoto.com

It happens in reading, and it happens in our lives, so it’s easy to see why Westerners have trouble enjoying the simple pleasures of work, learning, studying, exercising, eating, and even spending time with loved ones—all because they do not engage in them mindfully. When was the last time you got out of your head and away from reliving your past or trying to plan out your future? When was the last time you actually tasted your lunch or exercised without the TV blaring? Inherently Western practices like these were modeled for us as little kids.

Our culture does not reinforce the advantages of staying in the moment.

It is this type of thinking that is anxiety provoking and interferes with the enjoyment of the moment at hand, which is the only moment that we truly have—a point Eckhart Tolle makes in his bestselling book, The Power of Now. As Tolle points out, looking back into the past will fill you with regrets, looking into the future will fill you with anxiety. Anyway, neither of those moments exists any longer. The only moment we truly have is now. In short, let go of attachments to any moment outside the present one.

MINDFULNESS TAKES PATIENCE TO LEARN—MY EARLY EXPERIENCE:

My early experiences with meditation were just as frustrating. I have practiced meditation for about 3 years now, enough to have gotten my brain wrapped around the process but still not long enough for it to always go smoothly. When I first began meditating, I would compare my own

“With a peaceful smile on his face, I pictured the monk engaging in long periods of undisturbed focus.

Not so for me!”

Photo courtesy of http://www.etsy.com/shop/beautyflows

experience of struggling to stay focused to that of a blissful, experienced Eastern practitioner, say a Buddhist monk. Comfortable in his yogic pose, with a peaceful smile on his face, I pictured the monk engaging in long periods of undisturbed focus. Not so for me! During my first several attempts, my fragmented mind would zoom off into all directions, like an explosion, with irretrievable mind-rubble scattered everywhere. I am getting agitated right now as I recall how anxious I would feel just anticipating being quiet and still in meditation for even 5 minutes.

Even though I struggled, I kept trying.

My particular practice has now evolved to sitting mindfully for 20 minutes every morning. I learned that it is okay when my mind scatters. If my mind takes off down yet another rabbit hole, I simply refocus my concentration and bring it back to the present moment again and again. During a session, even if I get a profound thought, I ignore it. I’ve learned that miraculously, those profound thoughts will return at a later time and so they won’t be wasted.

Eventually, I was rewarded with tiny, seconds-long periods of mindfulness that were effortless. I would describe these particular moments as a flow experience, like when a competing athlete is in the zone. These tiny intervals of mindful focus then began to coalesce and become progressively longer. Even now, if I get five truly mindful minutes from my 20 minute meditation session, I am satisfied.

It is the cycle of losing my focus and finding it over and over again that is essential to the process. What Ms. Pickert and I learned is this, and I cannot make this point strongly enough: the goal of mindful practice is not just to learn how to sustain concentration; rather, it is to learn how to ignore your thoughts.

The human mind loves to first, manufacture a problem in the form of a thought and to second, ponder it and solve it with the persistence of a dog chewing on a bone. And like that dog reflexively chewing, the rumination that results when your brain locks onto a thought can become a trap leading to an endless, mindless loop. That’s why practicing mindfulness is key to breaking this habitual

“And like that dog reflexively chewing, the rumination that results when your brain locks onto a thought can become a trap resulting in an endless, mindless loop.”

Photo purchased from iStockphoto.com

obsessive-thinking pattern. The chief goal of mindfulness is instead to let your thoughts just come, and then, to simply ignore them—all the while, to keep bringing your focus back to your center. By the “center,” I mean the moment you are in with its bounty of sensations like sounds, smells, tactile sensations, and your breathing. While meditating, a meditation-mentor explained to me that even the feeling in my big toe is more important than allowing my mind to wander off into its chaos and tyrannical thoughts.

It is through this process of repeatedly reigning in your mind after it involuntarily leaves its focus, and then gently bringing it back to its peaceful quiet center, that your mind learns to reflexively do this in the real world too. This learned reflex is especially important during times of stress. Your mindfulness practice teaches your mind to adopt a new default operating system: one of calm instead of one suffering from surges of adrenalin. Through the restructuring that happens because of neuroplasticity, it’s been proven that your practice can actually replace the accrued damage done by stress, trauma, and constant distraction.

Meditation is hard work for me. I don’t reap any rewards during the actual meditation session; but rather, just like growth in a garden, its rewards are appreciated in slow, regular, and steady growth over time. What’s required for a garden to flourish? It needs regular watering (a regular mindful practice) and cultivation (meditation), continually pulling the weeds (ignoring distracting thoughts), and fertilizing (no matter how difficult, returning to the mind’s peaceful center). There’s no quick way to cultivate mindfulness—sorry Westerners!

Through my meditation practice, I’m learning to be still and simply be in the moment.

Our brain has the ability to rewire itself through meditation. The research[1] suggests there are concrete and provable benefits to exercising the brain through meditation. Many cognitive therapists recommend MBSR to patients as a way to help cope with anxiety and depression. In short, it’s an effective method to deal with stress.

THAT VOICE INSIDE YOUR HEAD—YOU KNOW, THE ONE THAT WON’T SHUT UP:

Instead of a knee-jerk anxiety reaction to stress, your brain has the ability to be retrained to respond differently: instead of reflexively stepping on the gas when faced with stressful situations, it can be taught instead to pull back, which is what Michael Singer advocates in his book, The Untethered Soul. He begins by challenging us to analyze the mental dialogue that goes on, non-stop, inside each of our heads:

In case you haven’t noticed, you have a mental dialogue going on inside your head that never stops. It just keeps going and going. Have you ever wondered why it talks in there? How does it decide what to say and when to say it? How much of what it says turns out to be true? How much of what it says is even important? And if right now you are hearing, “I don’t know what you’re talking about. I don’t have any voice inside my head!”—that’s the voice we’re talking about. ~ Michael Singer

The trouble with this voice, explains Michael Singer, is that we tend to be too close to be objective—especially when it starts in with all its negative feedback. He calls that voice inside your head your “inner roommate,” who for the most part is a bad roommate—one who brings nothing but negativity into your consciousness and who won’t shut up. Unlike a bad roommate however, because this voice is inside your own head, you can’t get away from it—you can’t call-block it, evict it, or un-friend it on Facebook. Singer explains that the best way to distance yourself from its incessant chatter is to step back and view it objectively:

“There is nothing more important to true growth than realizing that you are not the voice of the mind—you are the one who hears it. . . If you watch it objectively, you will come to see that much of what the voice says is meaningless. . . It’s the commotion the mind makes about life that really causes the problems.” ~ Michael Singer

ADVICE FOR STRESSED-OUT APPLICANTS:

I routinely communicate with panicking applicants who are preparing to take the OAT, often for the second and third time. Over-identified with and therefore enmeshed in their negative thoughts, they are setting themselves up for certain failure by imagining every step of white-knuckling their way through retaking the OAT. Their bad roommate is onboard, yapping away, and reminding them of not only their past failures but also, just how bad they are at objective test-taking.

It doesn’t have to be this way!

My reason for writing this article and what I want anxious applicants to learn is this: you are NOT the voice inside your head! I agree with Singer: you are not your thoughts. Get a handle on this negative voice! Instead of going full speed ahead in panic mode, Singer recommends that you instead pull back, or lean away. You drop back to collect yourself, and take back your center. Through this method, you will create objectivity; create a space where you can get some distance—it’s the only way to ignore the negative voice inside your head. You will not be able to get rid of it, but instead, just like you practice in meditation, you let the negative thoughts from your inner voice just come and then go—in short, you ignore them.

My reason for writing this article and what I want anxious applicants to learn is this: you are NOT the voice inside your head! I agree with Singer: you are not your thoughts. Get a handle on this negative voice! Instead of going full speed ahead in panic mode, Singer recommends that you instead pull back, or lean away. You drop back to collect yourself, and take back your center. Through this method, you will create objectivity; create a space where you can get some distance—it’s the only way to ignore the negative voice inside your head. You will not be able to get rid of it, but instead, just like you practice in meditation, you let the negative thoughts from your inner voice just come and then go—in short, you ignore them.

As you work through the various aspects of the admissions process in the heat of battle, you have two choices: you can be like the soldier on the front line, jacked-up on adrenalin, who can only react to the chaos pressing in until he or she is exhausted or worse. Or, you can be like the commanding general up on the hill, astride a horse and with binoculars, calmly viewing the entire battlefront. From this perspective, you are able to see the entire conflict and instead, can strategize—you are able to respond rather than just react. You are still doing battle with the OAT, but you have your inner voice in check, and you react to the OAT test-taking process with a calm center and confidence in your preparation.

Singer explains the fault he finds with Western thinking: to generate change on the inside, you cannot just rearrange things on the outside. To begin this process of changing your inside, namely your mind, you need to develop what Eckhart Tolle calls a “Watcher.” The way I think of this concept is to use the word picture of a security camera. In my meditation practice, I imagine myself watching my mind on a security camera, which is the best technique I know to visualize myself from a remote perspective and therefore, looking at myself objectively with the remoteness that Singer recommends. The security camera acts as my Watcher, creating the space I need to separate from my thoughts and be able to look at them objectively and without all their drama. I routinely use this practice during meditation to calm myself and thus sit in tension with those thoughts, let them come into my consciousness-stream, parade by and then pass, and make their exit out the other side of my awareness as I calmly prompt my mind to return to its quiet center. My thoughts appear on the camera and then I watch them exit out the left side, much like actors leaving a stage when the drama is over. I do this over and over. I don’t block my negative thoughts; instead, I invite them to appear on my Watcher’s security camera. I take a look at them like they are the Boogie Man, and then watch as they lose their power over me and slowly disappear.

Another technique I use outside of meditation is Deepak Chopra’s “STOP.” 1) When an overwhelming feeling strikes, the first thing you do is “S” for stop: discontinue what you are doing and get in the moment. 2) Next, the “T” stands for taking three deep breaths from your lower diaphragm, which will automatically relax your body. 3) Then, you “O” or observe in your body where you are feeling the feelings—whether they be anxiety, anger, depression…etc. This would be in the form of any feeling that is dragging you out of your seat of consciousness and into over-identification with the drama inherent in the situation that’s causing you to react. For example, tension and anxiety are commonly felt in the throat or the chest. 4) Finally, there is “P,” which stands for “proceeding with grace,” meaning that you have regrouped enough to continue along peacefully with your business after being regrounded in the moment. It looks like this:

- S is for “stop what you are doing”

- T is for “take 3 deep breaths”

- O is for “observe where in your body you are feeling the feelings”

- P is for “proceed and resume your normal activity after regrounding”

DEVELOP YOUR OWN PRACTICE:

It’s not within the scope of this article to explain the entire process you need to undergo to gain a mindfulness perspective. My advice is to take from the wisdom of the Time Magazine article and Michael Singer: develop your own practice, one that will slowly help you achieve the objectivity required to separate from that negative internal voice.

“Matt, is a 4th year medical student who has adopted mindfulness practices for himself and is writing a blog about his experiences.”

Matt, is a 4th year medical student who has adopted mindfulness practices for himself and is writing a blog about his experiences. In the “About Me” section, he explains how he uses mindfulness practices to deal with his own struggle with OCD and anxiety. I highly recommend the Mindfulness MD reading list.

Mindfulness involves developing a practice that re-trains your brain to respond to anxiety with a wholly different reaction. Rather than reacting with anxious adrenalin physiology and doomsday thinking, you can teach yourself to react by pulling back, avoiding that wave of sickening anxiety that makes you want to throw-up.

To get to this place where you can ignore your thoughts and retrain your brain to respond differently to a stress stimulus, you must engage in a regular practice. That’s the work you must do.

I do my 20 minute meditation sit in the morning because, in the evening, I am too hyped up on the day’s activity to even begin clearing and centering my mind. I spend the first 3-5 minutes just focusing on my breathing, to get it rhythmic and natural. I then focus my vision on the back of my eyelids and use the technique of the Watcher in the form of the security camera I mentioned earlier. Sometimes I imagine I am on the shore of a gently running river, and my thoughts are moving like a boat would from right to left on the security camera of my mind. They gently come into view and I, from my safe vantage point on the shore, watch them sail by. I find that having my mind on the shore and my thoughts on the water prevents me from jumping onboard and rummaging around in the hold of my ship-of-negative-thoughts.

I intentionally use the words “gentle” and “peaceful” when I refer to this process because that is the tone, the attitude you must take with your thoughts, the good ones and the bad ones, as they make their appearance in your mind’s eye. The very act of your brain presenting these thoughts to your consciousness comes from the trust your brain has in your practice, the safe haven you’ve created, where those thoughts can be offered forth. Your part of the bargain is to remain calm and peaceful, breathing in and out, and showing that you are worthy of your brain’s trust by not freaking out. It is through this dress rehearsal of ignoring your thoughts that you can then apply this very practice in your real life when anxiety strikes.

Properly conditioned by your regular mindfulness practice, your brain responds rather than reacts—responding in the peaceful manner that you have reconditioned it to employ. Simply put, you stop reflexively freaking out and instead, your first response is one of relaxing into the anxiety, waiting for it to pass.

As you begin developing your practice, adjust your expectations and take it slow.

My Recommendation on How to Get Started Developing Your Own Practice:

To get started with any process that’s unfamiliar, I’m a big believer in using a cookbook approach, that is, to use a tried and true method that has worked for someone else. I’m going to give you one to try, knowing that if you’re like me, and as you delve deeper, you’ll modify it to suit your developing philosophy.

I was introduced to meditation by Father Thomas Keating, a modern day contemplative, and so my practice is heavily influenced by the method he teaches. I’m going to modify it along with the Eastern practice recommended by our medical school student, Matt, and give you a basic cookbook approach that I think may work for you:

- Find a place where you can be alone and not interrupted. If you live with other people, I recommend being behind a closed door.

- To begin, set a timer for 10 minutes. Using a timer will help you not to be distracted by wondering what time it is. Progressively increase the time until you can sit mindfully for 20 minutes.

- Sit in a chair with a back on it, upright, with your palms turned down, resting on your knees. Don’t lean back in the chair because you don’t want to fall asleep. Keep your spine gently straight.

- Close your eyes and put a slight smile on your face. It’s amazing how this adjusts your attitude to begin, and reminds you to be grateful for this time you have to indulge in this practice.

- Begin breathing through your nose, deeply, and gently. Let your lower belly rise and fall with the slow breaths. Make a special effort to exhale completely. Feel and be mindful of the sensation the inhale and exhale makes at the tip of your nose.

- Employ a word or short phase that you will use repeatedly to refocus your mind when it wanders off, to bring it back to center. I use “be still.” After using it repeatedly, your mind and body will develop a conditioned response to the word/phrase, and will respond by relaxing.

- Focus on the back of your eyelids much like you’d view a movie screen in a dark theater. Imagine that you are watching this screen in anticipation of what will be projected on the screen next. Do this with an open mind and spirit.

- As thoughts and images appear on the screen, gently sweep them away by having them visually exit the screen. Being a PowerPoint fan, I imagine the transitions used in this format to advance to the next slide (i.e. fade, dissolve, swipe…etc.), and do the same for the screen-of-my-thoughts. No thought can linger or capture your thinking. All thoughts are sent down the stream of your consciousness.

- Repeat steps 5-8 until over and over until the timer goes off. Remember, if you get only one minute of mindfulness in that 10-20 minutes, your efforts paid off.

For my Christian audience members who may prefer a mindfulness practice that comes from their own tradition, access a description of mindfulness with Christians in mind.

I hope I’ve created an appetite that will motivate you to change and develop your own mindfulness practice. If your experience is like mine, it will change your life—and not just for taking objectives tests! It will help you with all the anxious feelings inherent in being a human in this hectic world in which we live.

I ONLY wish I had known how to cultivate mindfulness when I was your age…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Footnotes: [1]Pickert, Kate. 2014. Head Space. Time Magazine, February.

Evolving Recommended Reading List: http://www.mindfulnessmd.com/suggested-reading/

Article Bibliography:

Dyer, Wayne W. Change Your Thoughts, Change Your Life: Living the Wisdom of the Tao. Carlsbad, CA: Hay House, 2007

Hạnh, Nhất. The Long Road Turns to Joy: A Guide to Walking Meditation. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 2011.

Keating, Thomas. Invitation to Love: The Way of Christian Contemplation. New York: Continuum, 1995.

Singer, Michael A. The Untethered Soul: The Journey beyond Yourself. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 2007.

Tolle, Eckhart. The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2004.

Categories: Applying, Dr. Munroe's Recommended Reading, OAT

Thank you so much for writing such a wonderful, tactfully written, and informative article! I agree. Practicing mindfulness is a great way to “re-center” yourself and your priorities. I will admit, however, that I find that this meditation was so much easier when I was younger. As time goes on and more responsibilities pile up, it becomes more and more difficult to focus on the inner workings of your own mind. The times where I had the leisure to sit and enjoy the wanderings of my mind were more frequent when I was in high school and living with my parents. Now, as a pre-optometry student, working full-time and living on my own, it’s tough to find the time and motivation to do much meditating. Your article reminds me how significant it is to find the time and effort to do this. It’s true that our western culture is very “proactive” and result-oriented – we forget the importance of our own personal peace. At least I do manage to use this as my default stress relief. Succumbing to stress is quite unavoidable, but it doesn’t have to get the best of you. I am prone to migraines due to stress and I learned (the hard way) through the years on how to avoid them. I learned that in times before big projects, tests, or events, I find a moment to calm down, breath, and get myself to focus on my goals.

Thanks to your post promoting the mindfulnessMD blog at http://www.mindfulnessmd.com/2014/03/16/mindfulness-meets-life/, I learned to take it a step further. I would use this moment to remind myself what the best case scenario and worst case scenario would entail. Usually, when you actually tell yourself out loud what the worst case scenario is, you find yourself thinking “well, that’s not so miserable!” When you hear that nagging voice in your head saying the negative things out loud, it seems significantly less believable. I tell all my friends about it! Getting the word out on this is a great way to improve the quality of life of many people. At the very least, if we can improve our own lives, we will have a better, clear-headed path to be able to benefit the lives of those around us.

I would also like to express how glad I am that you have taken it upon yourself to help others such as myself and other stressed out pre-optometry students. I don’t think any of us can thank you enough for the time and effort you and your staff put into helping us. With your kindness (and information!) you have succeeded into making this application process much less stressful for every person who has had the honor of communicating with you.

Please continue your meditation. It’s obviously benefiting many more people than just yourself!

Dear Anna,

I don’t know HOW I failed to respond to your lovely and kind words of praise, but it looks like I did because I cannot find a reply. So sorry! Let me take the time to correct this now…

You’ve stated so eloquently all the thoughts and feelings I maintain about practicing mindfulness. Yes, it is NOT a quick fix as we Westerners impatiently expect. Yes, it can change the very way your brain functions. And yes, and EVEN most importantly, you learn to both recognize and thus ignore that negative voice in your head that does nothing to help you proceed to your desired goal.

I hope you have successfully navigated the admissions process into a program of your choice. Thank you again for taking the time to comment in such a thorough and thoughtful way.

Most Sincerely,

Jane Ann Munroe, OD, Assistant Dean of Admissions for SCCO